Some commentators were skeptical of Team Sky’s explanation for Chris Froome’s 80km tour-winning attack on stage 19 of the Giro. His success was put down to the detailed planning of nutrition throughout the ride, with staff positioned at strategic refuelling points along the entire route. If you consider how skeletal the riders look after two and a half weeks of relentless competition, along with the limits on what can be physically absorbed between stages, the nutrition story makes a lot of sense. Did Yates, Pinot and Aru dramatically fall by the wayside simply because they ran out of energy?

The best performing cyclists have excellent balancing skills. This includes the ability to match energy intake with energy demand. The pros benefit from teams of support staff monitoring every aspect of their nutrition and performance. However, many serious club-level cyclists pick up fads and snippets of information from social media or the cycling press that lead them to try out all kinds ideas, in an unscientific manner, in the hope of achieving an improvement in performance. Some of these activities have potentially harmful effects on the body.

Competitive riders can become obsessed with losing weight and sticking to extremely tough training schedules, leading to both short-term and long-term energy deficits that are detrimental to both health and performance. One of the physiological consequences can be a reduction in bone density, which is particularly significant for cyclists, who do not benefit from gravitational stress on bones, due to the non-weight-bearing nature of the sport. In a recent paper, colleagues at Durham University and I describe an approach for identifying male cyclists at risk of Relative Energy Deficit in Sport (RED-S).

You need a certain amount of energy simply to maintain normal life processes, but an athlete can force the body into a deficit in two ways: by intentionally or unintentionally restricting energy intake below the level required to meet demand or by increasing training load without a corresponding increase in fuelling.

Our bodies have a range of ways to deal with an energy deficit. For the average, slightly overweight casual cyclist, burning some fat is not a bad thing. However, most competitive cyclists are already very lean, making the physiological consequences of an energy deficit more serious. Changes arise in the endocrine system that controls the body’s hormones. Certain processes can shut down, such as female menstruation, and males can experience a reduction in testosterone. Sex steroids are important for maintaining healthy bones. In our study of 50 male competitive cyclists, the average bone density in the lumbar spine, measured by DXA scan, was significantly below normal. Some relatively young cyclists had the bones of a 70 year old man!

The key variable associated with poor bone health was low energy availability, i.e. male cyclists exhibiting RED-S. These riders were identified using a questionnaire followed by an interview with a Sports Endocrinologist. The purpose of the interview was to go through the responses in more detail, as most people have a tendency to put a positive spin on their answers. There were two important warning signs.

- Long-term energy deficit: a prolonged significant weight reduction to achieve “race weight”

- Short-term energy deficit: one or more fasted rides per week

Among riders with low energy availability, bone density was not so bad for those who had previously engaged in a weight-bearing sport, such as running. For cyclists with adequate energy availability, those with vey low levels of vitamin D had weaker bones. Across the 50 cyclists, most had vitamin D levels below the level of 90 nmol/L recommended for athletes, including some who were taking vitamin D supplements, but clearly not enough. Studies have shown that the advantages of athletes taking vitamin D supplements include better bone health, improved immunity and stronger muscles, so why wouldn’t you?

In terms of performance, British Cycling race category was positively related with a rider’s power to weight ratio, evaluated by 60 minute FTP per kg (FTP60/kg). Out of all the measured variables, including questionnaire responses, blood tests, bone density and body composition, the strongest association with FTP60/kg was the number of weekly training hours. There was no significant relationship between percentage body fat and FTP60/kg. So if you want to improve performance, rather than starving yourself in the hope of losing body fat, you are better off getting on your bike and training with adequate fuelling.

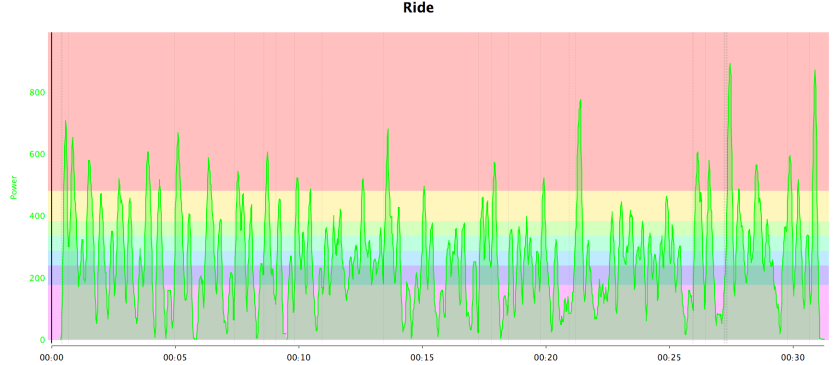

Cyclists using power meters have the advantage of knowing exactly how many calories they have used on every ride. In addition to taking on fuel during the ride, especially when racing, the greatest benefits accrue from having a recovery drink and some food immediately after completing rides of more than one hour.

For those wishing to know more about RED-S, the British Association of Sports and Exercise Medicine has provided a web resource.

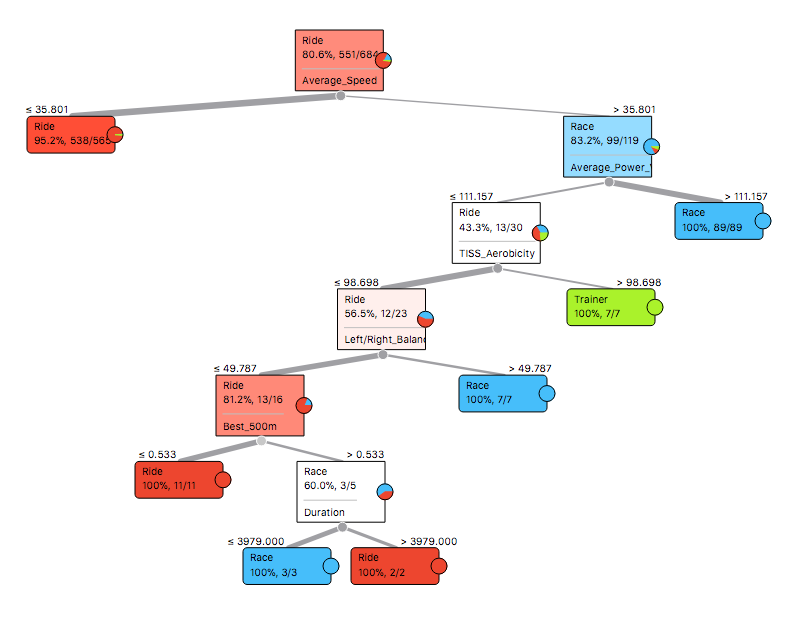

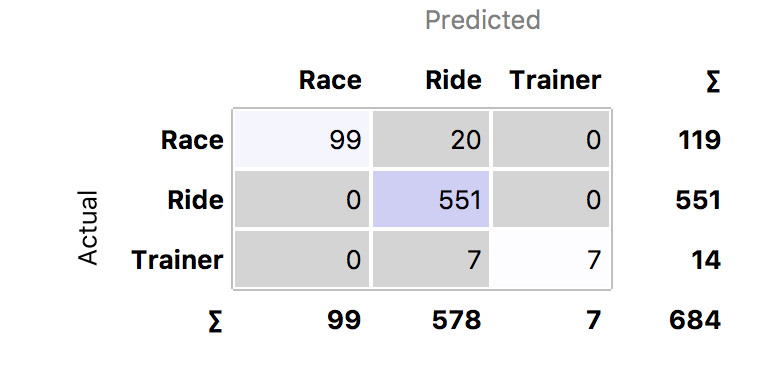

A related blog will explore the machine learning and statistical techniques used to analyse the data for this study.

References

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, British Association of Sports and Exercise Medicine

Synergistic interactions of steroid hormones, British Journal of Sports Medicine

Cyclists: Make No Bones About It, British Journal of Sports Medicine

Male Cyclists: bones, body composition, nutrition, performance, British Journal of Sports Medicine

In the

In the