Amid the fanfare about the extraordinary AI capabilities of large language models (LLMs), the race is on to produce LLM applications that actually do something useful. Several hurdles obstruct the way forward, including confabulation, privacy and limitations of training data. This article explains how Retrieval-Augmented Generation can address some of these issues and help find out some useful information about cycling.

Confabulation

Since they are trained only to predict the next word in a sentence, LLMs have no understanding of the text they generate. They can have a tendency to intersperse facts with inaccurate or untrue statements in a manner that seems entirely plausible and convincing. You should not rely on an LLM for advice on important decisions without validating its response. Note that if you ask an LLM for its sources, the citations may be imaginary or if they exist the references may not support the assertions.

One way to reduce the risk of confabulation is to ask the LLM to base its answer selected relevant documents.

Privacy

If you use an online ChatBot, everything you type or upload is stored on the provider’s server. This can be used as further training data or for snooping on users. There is a significant risk that a lot of personal and proprietary company information has already been hoovered up in this way. Companies need ways to sandbox internally developed LLM tools that contain sensitive data and prevent leakage of confidential information.

Privacy can be addressed by running LLMs on local networks. This is possible because inference is a simple task relative to training, which requires banks of data servers. Many free open-source models are available. Running an open-source model locally also avoids paying a subscription to an online provider.

Limitations of training data

LLMs are trained on vast generic data sets. This is a very expensive task, so they are typically frozen at some point in time. If you ask an LLM about current news events, it will typically tell you that it was trained on data up to a certain date in the past and has no knowledge of the event. The models may also lack specialised data in narrow domains.

RAG provides a way to supplement the original training set with selected additional information relevant to the field of interest.

RAG

Retrieval-Augmented Generation is an approach that provides an LLM with additional information to help it answer a query. For example, when asked about current affairs, it would be very helpful to retrieve a copy of today’s newspaper. Companies may wish to develop LLM-based applications with specialist knowledge of internal documentation. RAG makes this possible.

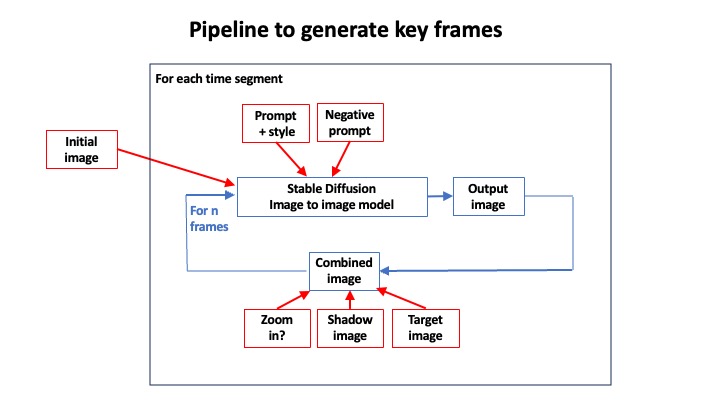

When you interact with an LLM, your conversation is presented to the model in the form of a huge string of numbers called an embedding. LLMs are trained so that sentences with similar words and meanings have similar embeddings. The idea of RAG is to take one or more relevant supplementary documents, split them up into chunks and store the embeddings of these chunks in a vector database. When a user presents a query, the database retrieves the embeddings of chunks that most closely match the query. In this way, the query can be augmented with relevant chunks of text from the source material. Note that this avoids the need to do additional expensive training or fine-tuning of the LLM on specialist topics.

One weakness of RAG is that most LLMs have not been trained specifically on the types of prompts used in RAG, though some companies, like Cohere, are working on this.

Cycling Through the Pandemic

I decided to try this out using a freely available book called Cycling Through the Pandemic, which has the slightly cryptic subtitle, Tactical Urbanism and the Implementation of Pop-Up Bike Lanes in the Time of COVID-19. This 250-page book was published in 2024, so it could not have been part of the training set for the LLM that I was using.

It is unbelievably easy to download and then run an open-source LLM on your local machine. All you need to do is download LM Studio. I decided to use an open-source LLM model called Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF. I dragged and dropped the pdf of the book into the chat-box and started asking questions.

A transcript of my conversation is recorded below. At each step, LM Studio retrieved three chunks of text from the book it considered most relevant to the query, allowing me to check the reliability of the model’s interpretation.

The model answered in good English, basing its responses on the content of the book. It corrected itself when challenged on the claim that Bogotá is in France. It even responded in French to a question posed in French. In my view, RAG can be used to produce genuinely useful applications for LLMs.

RAG dialogue based on a book about the impact of COVID 19 on cycling

You

CyclingCOVID.pdf

What is tactical urbanism

Assistant

Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF

Intermediate steps hidden. Click to expand.

Based on the provided information, tactical urbanism refers to a type of urban planning that involves temporary and low-cost interventions aimed at introducing rapid changes to urban spaces with a broader purpose in mind (Lydon and Garcia 2015). It can be seen as a practical approach to urban change where many small actions implemented at the hyper-local level can achieve longer-term goals of creating a liveable, walkable, sustainable community.

Tactical urbanism often involves shortcuts or rapid and unbureaucratic actions taken by municipalities in response to crises (Citation 1). It can be associated with grassroots initiatives but can also be used by authorities. This approach has been implemented in various contexts, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tactical urbanism is characterized by its focus on temporary and flexible material approaches to urban change, which can be both a practical tool for citizens and enterprising governments alike (Citation 3).

It’s worth noting that there are different perspectives on tactical urbanism, with some viewing it as a means of achieving substantive change without state action, while others see the increasing professionalization of these activities as borrowing their material design language (Citation 2).

You

Why was cycling boosted by COVID 19?

Assistant

Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF

Retrieved 3 relevant citations for user query

Done predicting

Cycling saw a boost during the COVID-19 pandemic for several reasons (Citation 2). Firstly, people had less need to travel due to home working and distance learning. Secondly, the fear of infection led to a strong decline in ridership on public transport, which benefited cycling. Additionally, active mobilities such as cycling were promoted as a means of staying fit and getting exercise when other recreational facilities were closed.

The pandemic also led to an increase in cycling for leisure activities (Buehler and Pucher 2021b), with the strongest increase seen on weekends and in the afternoon. This shift towards cycling as a leisure activity is likely due to the rise of “undirected travel,” or trips without a specific destination, which was encouraged by social distancing measures.

In France, for instance, the first COVID-19 related lockdown led to a rapid increase in cycling use (Buehler and Pucher 2022) and implemented temporary cycle paths. Governments saw cycling as a solution to develop health-friendly mobility while responding to the possible desertion of public transport due to fear of catching the virus (Citation 3).

You

Has the COVID related boost in cycling persisted

Assistant

Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF

Retrieved 3 relevant citations for user query

Done predicting

The survey conducted in Geneva and Lausanne (Rérat et al. 2022; Schmassman and Rérat 2022) found that the COVID-related boost in cycling has largely persisted. The majority of respondents reported cycling as much or more often than before the pandemic, with a significant number even starting to cycle for the first time.

In Geneva, 42% of respondents cycled as much as before, while 44% cycled more often. In Lausanne, 58% cycled as much as before, and 27% cycled more often. This suggests that many people have adopted cycling as a mode of transport during the pandemic and are likely to continue using it.

The fact that 81% of respondents in Geneva (73% in Lausanne) agree or strongly agree that COVID cycle lanes make them feel safer also suggests that these temporary infrastructure projects had a lasting impact on cyclist safety and behavior.

However, as mentioned by Citation 2, the long-term sustainability of this boost is still uncertain. The study notes that most cycling infrastructure implemented during the pandemic involved existing projects, and it remains to be seen whether this “leap forward” will make a lasting difference in the trajectory of local public action or simply represent a spike on an upward graph.

Overall, while there are indications that the COVID-related boost in cycling has largely persisted, further analysis is needed to determine its long-term impact.

You

What has been the impact specifically in London?

Assistant

Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF

Retrieved 3 relevant citations for user query

Done predicting

The impact of temporary cycling infrastructure and “Tactical Urbanist” approaches in London is a complex issue with both positive and negative effects.

Positive impacts include:

The introduction of School Streets, which have shown to promote mode shift towards active modes of travel (Hopkinson et al. 2021) and improve air quality at schools (Air Quality Consultants 2021).

The implementation of temporary cycle lanes and other small-scale projects aimed at improving the smaller residential or local streets in London.

These efforts are part of the Healthy Streets approach, which aims to promote a more sustainable transportation system in London.

However, there have also been negative impacts, including:

Variable outcomes between sites, with some schemes showing little effect (Citation 2).

Criticisms that some projects were implemented too quickly or without adequate consultation, leading to concerns about the speed and process of decision-making.

Vandalism of planters, bollards, and cameras used to prevent through-traffic in some areas (Citation 3).

Removal of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, especially in Outer London, due to opposition from local residents.

The Temporary City report by Asa Thomas highlights the importance of balancing big change with small impact, emphasizing the need for careful planning and consultation when implementing new transportation projects.

You

What research was done in French cities?

Assistant

Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF

Retrieved 3 relevant citations for user query

Done predicting

The research on French cities during the COVID-19 pandemic focused on understanding how urban planners and policymakers implemented measures to promote cycling and improve public transportation.

A study examined five French cities: Grenoble, Lyon, Montpellier, Rennes, and Bogotá (Citation 1). The study found that these cities had varying levels of population size, density, and surface area. For example, Bogotá was the most populous city with over 7 million inhabitants, while Grenoble had a smaller population of around 160,000.

Another study looked at the implementation of measures in French cities during the pandemic (Citation 2). The research found that some cities focused on improving cycling infrastructure within the city center, such as Lyon and Rennes. In contrast, other cities prioritized links between periurban municipalities or outer suburbs.

A book titled “Changing Bikeability: Everyday Cycling in Developed Territories” explores changing bikeability in French cities during the pandemic (Citation 3). The book examines six French cities: Grenoble, Lyon, Montpellier, Paris, Rennes, and Saint-Étienne. The research found that each city had its unique characteristics and ways of implementing measures to promote cycling.

These studies provide insights into how different types of cities implemented measures to improve cycling infrastructure during the pandemic, and whether these measures were made permanent.

You

Is Bogotá in France?

Assistant

Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF

Retrieved 3 relevant citations for user query

Done predicting

No, Bogotá is not in France. According to Citation 1 and Citation 2, Bogotá is located in Colombia, and it has been compared with four French cities: Grenoble, Lyon, Montpellier, and Rennes.

In fact, the study mentioned in Citation 3 compares the cycling infrastructure in these four French cities (Grenoble, Lyon, Montpellier, and Rennes) with that of Bogotá, a city located in Colombia.

You

Quels ont été les résultats à Grenoble ?

Assistant

Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF

Retrieved 1 relevant citations for user query

Done predicting

Les résultats obtenus à Grenoble sont mentionnés dans la citation :

“Nous avons contacté le Syndicat Mixte des Mobilités de l’Aire Grenobloise et réussi à obtenir la base de données du réseau cyclable. De plus, un stagiaire a effectué une interview avec un technicien de cette organisation, et sur plusieurs occasions, il est allé visiter le site pour voir si les voies temporaires (pop-up tracks) existaient toujours.”

Cela indique que les auteurs ont réussi à collecter des données sur le réseau cyclable de Grenoble en contactant la Syndicat Mixte des Mobilités de l’Aire Grenobloise et en effectuant une interview avec un technicien. Cependant, il n’y a pas d’information sur les résultats concrets de ces efforts.

Cependant, on peut trouver plus d’informations dans le graphique (Figure 8.2) qui montre différents types de voies temporaires installés dans les cinq villes étudiées, dont Grenoble.

39.77 tok/sec

•

234 tokens

•

3.34s to first token

•

Stop: eosFound