A high-performance bicycle relies of a mix of advanced polymer science and metallurgy. Carbon only makes up about the half the mass of a carbon-framed bike. The moving components include iron, aluminium and specialist alloys. The frame is held together with epoxy resins and the tyres include a range of compounds to reduce rolling resistance, while maintaining grip. I wondered, what is the chemical composition of my bicycle? Where do these chemicals come from?

Canyon frameset and deep-section wheels

The primary materials of the frame and rims are carbon fibre and epoxy resin. High-end frames and rims use “pre-preg” carbon filaments held together by a thermosetting resin matrix. Carbon fibre is roughly 95% elemental carbon. It is created by heating precursor fibres until only carbon remains in a hexagonal crystalline structure. Epoxy resin is polymer typically derived from carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. It provides the compressive strength that keeps the carbon fibres in shape.

Estimated Mass: ~2.8 kg (Frame, Fork, Rims).

Elemental makeup: ~80% Carbon, ~12% Oxygen, ~7% Hydrogen, ~1% Nitrogen.

Shimano Ultegra drivetrain

The drivetrain is made out of aluminium alloys, stainless steel and small amounts of titanium/chrome. The cranks and hubs require high-strength aluminium alloys that include zinc and magnesium to prevent fatigue. The cassette and chain are mostly chromium-steel. The chain requires high tensile strength and wear resistance, achieved through iron alloyed with carbon and chromium. Bearings are steel (iron/chromium) or occasionally ceramic (silicon nitride).

Estimated Mass: ~2.6 kg.

Elemental makeup: ~65% Iron, ~30% Aluminium, ~3% Chromium, ~2% Zinc/Magnesium/Others.

Continental GP5000 Tyres

Tyres are made from synthetic/natural rubber, silica and carbon black, a reinforcing agent. The GP5000 is famous for its “Black Chili” compound. Unlike older tyres that relied heavily on carbon black, modern high-performance tyres use a high percentage of silica to reduce rolling resistance while maintaining grip. The casing is usually nylon (polyamide), consisting of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and hydrogen. The bead is often Kevlar (aramid), which is another nitrogen-rich polymer.

Estimated Mass: ~0.5 kg (for the pair).

Elemental makeup: ~60% Carbon, ~20% Silicon, ~10% Oxygen, ~5% Sulphur (used in vulcanization), ~5% Hydrogen/Nitrogen

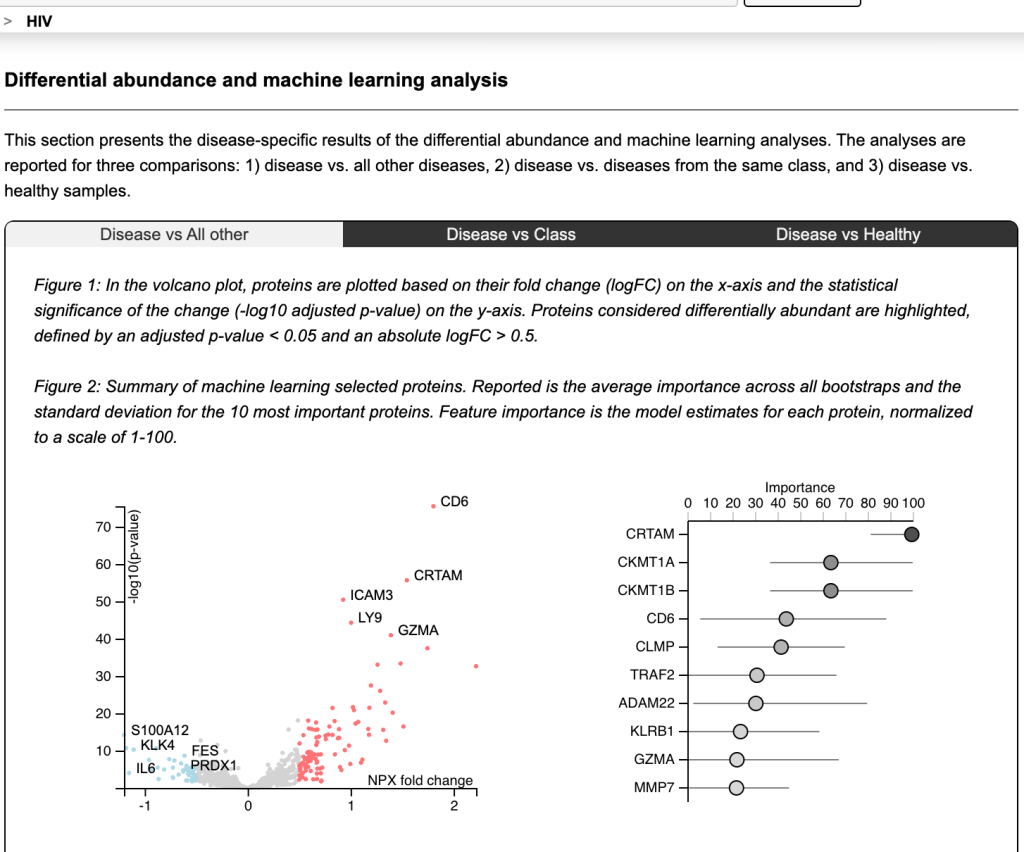

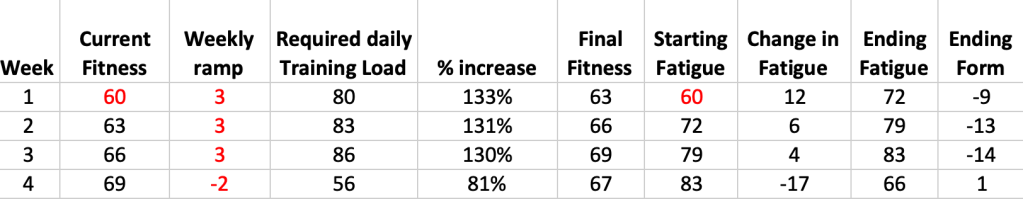

Total Elemental Breakdown (By Mass)

This table estimates the elemental distribution for a complete 8,000g (8kg) bike. These figures are calculated based on the average weight of the components listed above.

| Element | Estimated Mass (g) | % of Total | Primary Source |

| Carbon | 3,840g | 48.0% | Frame, wheels, tyres, resins, saddle |

| Iron | 1,760g | 22.0% | Chain, cassette, spokes, bearings, bolts |

| Aluminium | 1,440g | 18.0% | Crankset, hubs, stem, bars, calipers |

| Oxygen | 400g | 5.0% | Epoxy resins, rubber compounds, paint |

| Hydrogen | 240g | 3.0% | Polymer chains in resins and plastics |

| Silicon | 120g | 1.5% | Tyre compound (Silica), lubricants |

| Chromium | 80g | 1.0% | Stainless steel hardening (Drivetrain) |

| Nitrogen | 40g | 0.5% | Nylon tyre casing, Kevlar beads |

| Sulphur | 40g | 0.5% | Vulcanising agent in tyres and tubes |

| Others (Zn, Mg, Ti, Cu) | 40g | 0.5% | Aluminium alloying and specialty bolts |

| Total | 8,000g | 100% |

Where do these elements come from?

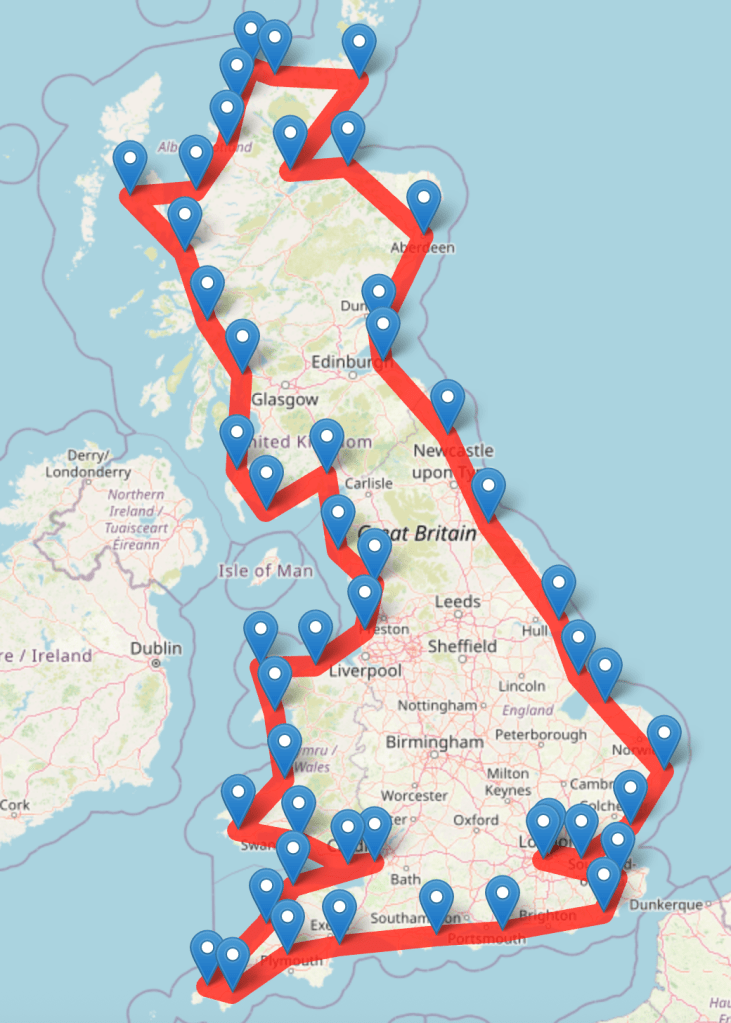

A fascinating paper by Craig Tindale, “The Return of Matter”, provides a sobering perspective on the dependency of manufacturers on the dirty and energy-intensive business of refining, purifying and separating the elements required for modern engineering and technology. While a Canyon bikes are designed in Germany and its Shimano components are engineered in Japan, the material reality of the bike is heavily dependent on Chinese industrial processing to turn the raw ore into high-purity metals and polymers.

Here is how this bike’s elemental components are tied to Chinese supply chains:

1. Carbon (48.0% of Mass)

Component: Frame, Wheels, Resins.

Dependency: High.

While the article focuses on metals, it notes that China has spent decades building the “processing sovereignty” required for advanced materials. High-modulus carbon fibre and the epoxy resins that bind them are part of a complex polymer supply chain where China acts as a global gatekeeper. Even if the precursor chemicals are sourced elsewhere, the massive scale of carbon fibre “midstream” production is increasingly concentrated in China.

2. Iron/Steel (22.0% of Mass)

Component: Chain, Cassette, Spokes, Bearings.

Dependency: Total.

Tindale describes an “Iron Ore Stranglehold”. Even though Western majors like BHP and Rio Tinto mine the ore, it is shipped as concentrate directly to Chinese smelters. The steel in your Ultegra cassette is likely refined in a Chinese furnace that sets the global “tempo of Western inflation” and availability.

3. Aluminium (18.0% of Mass)

Component: Crankset, Hubs, Cockpit.

Dependency: Extreme (60% share).

China controls approximately 60% of global aluminium smelting. Furthermore, high-performance aluminium (like the 7000-series in your cranks) requires magnesium for hardening. China controls 90–95% of global magnesium smelting. Without Chinese magnesium, your bike’s aluminium components would lack the fatigue resistance necessary for racing.

4. Silicon (1.5% of Mass)

Component: Tires (Silica), Lubricants.

Dependency: Dominant (95% share).

The refining of silicon is a massive Chinese monopoly; they control 95% of the world’s polysilicon capacity. While your tyres use silica , the high-purity chemical processing required for the “Black Chili” compound sits firmly behind what Tindale calls China’s “lattice of chemical plants”.

5. Chromium & Others (Mg, Ti, Cu) (2.0% of Mass)

Component: Stainless steel, Alloying, Bolts.

Dependency: Structural (The “Derivative Mineral Trap”).

Titanium is used in high-end bolts and derailleur parts. China and Russia control 75% of global titanium sponge capacity. The US has only one domestic plant, leaving bike manufacturers with almost no non-adversarial choice for titanium. Chromium and other alloy ingredients are often recovered as “hitchhikers” during the smelting of host metals. Since China dominates base metal smelting (e.g., 50% of copper), it essentially “inherits” the critical by-products needed to harden your bike’s drivetrain.

Summary: The “Bicycle Trap”

You might “own” the bike, while Canyon and Shimano might “own” the design, but the kinetic power—the ability to actually build the machine—belongs to whoever owns the refineries. If China were to tighten export controls, as it has recently done for antimony (ammunition) and tungsten (munitions), the production of high-performance bikes would likely experience a “forced regression in engineering capabilities”, where manufacturers would have to substitute inferior, heavier materials for the refined ones they can no longer access.