This morning I cheered on Bernard Bunting as he embarked on an epic tour Round Britain By Bike to raise money for the Rare Dementia Support Centre.

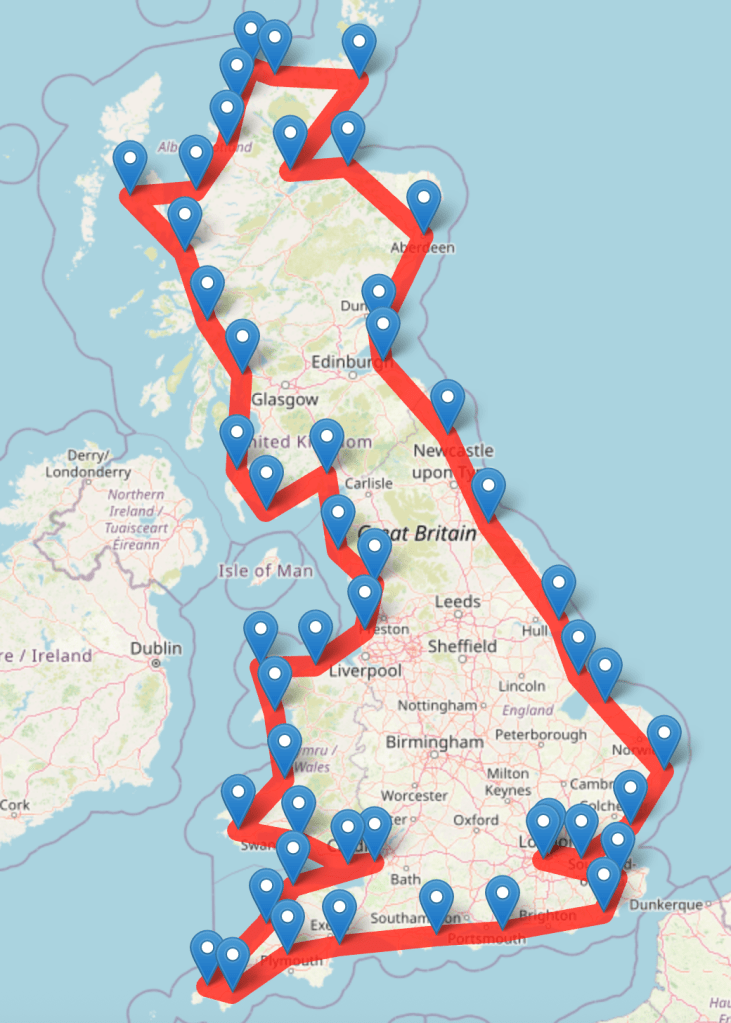

Bernard has set himself the impressive target of riding around the coastline of Britain. He will start and end at Putney Bridge in London, visiting 50 checkpoints along the way. This involves some serious route planning. The problem reminded me of the famous Travelling Salesmen Problem, where the challenge is to find the shortest route that visits each of a list of cities and returns to the starting point.

Travelling Salesman Problem

Apart from cycling around Britain, the Travelling Salesman Problem is relevant in to circumstances, such as scheduling the order of supermarket deliveries or planning logistics for manufacturing processes. The problem is considered to be NP-hard, meaning that the number of combinations explodes exponentially as the number of cities increases. For example, considering only the order in which he passes the checkpoints, Bernard could set off for any of 49 destinations, then choose to go to any of 48 places, then one of the remaining 47 … before eventually returning to Putney Bridge, resulting in 49! (approximately 6.1 x 1062) possible routes. This makes it very hard to be absolutely sure that any particular route is the shortest. For most problems the best you can do is come up with a fairly good route.

Elastic band – a greedy approach

I have always imagined a quick way to find a reasonably good approach is to visualise the cities marked with pins on a map. You start by putting an elastic band around the outside (a convex hull). Then you consider all the points inside the band and pull the elastic in around the closest point. Repeat until you have all the points. This is approach is “greedy” in the sense that it only looks one step ahead when choosing the best option. It starts slowly, but gets faster as the number of remaining points is reduced.

Tweaking it

One problem with the simple greedy approach is that it sometime produces a path that crosses itself. This is inefficient because it is alway an uncrossed path as always shorter. Although it is very easy to spot a crossed path, writing an algorithm that makes sure no path crosses any other is quite time-consuming. A simpler approach is to step around the current route and reuse the original trick of finding the closest point to each edge. If it is better to divert to that point, update the route. Repeat until no improvements are found. Tweaking the route around Britain slightly reduced the overall length.

This is the tweaking process running on a more complicated problem involving 300 checkpoints. Once the initial route is built, the tweaking process reduces the path length from 15.01 to 14.44. Python code can be found on GitHub in my TSP repository.

Getting real

Although tweaking the result shortened the route around the 50 British checkpoints, it does not follow the coastline and it jumps directly from St Ives to Johnston in Wales. So this solution is not particularly useful for Bernard’s planning. Practical route finding must take account of roads and physical barriers.

Fortunately Bernard will be following his GPS route on his bike computer. He also has a printed card for each day. Let’s hope he doesn’t get lost.

You can follow Bernard on Strava and news will be posted on his website. Please consider supporting Bernard by making a donation.